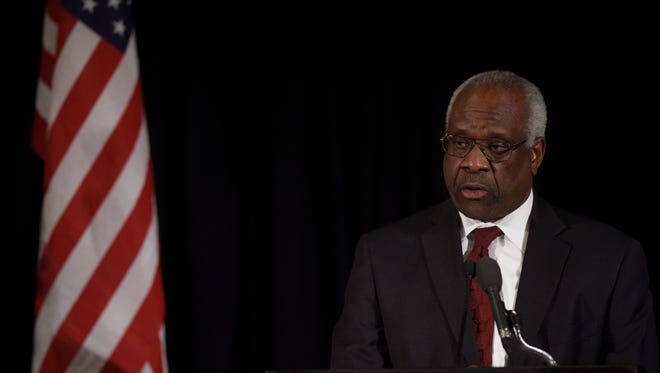

After 25 years, Clarence Thomas still dissents

WASHINGTON — Clarence Thomas enters his second quarter-century on the Supreme Court next week much like he began his first — in dissent.

The high court has changed, however, and that gives the nation's second African-American justice a new role to play. Gone is his ideological soulmate, the late Antonin Scalia. Ahead, pending next month's election, may be the court's first liberal majority in nearly 50 years.

Supreme Court faces historic transformation after election

That could make Thomas — a happy legal warrior among friends and allies, yet to the public an enigmatic loner — less powerful but more influential for the remainder of his career. And quite a career it could turn out to be: Having joined the court at 43, he would be the longest-serving justice in history before turning 80.

Just don't look for him to change.

"It is a bigger burden on him now," says Christopher Landau, an appellate lawyer who clerked for Thomas during his first term in 1991-92. "After 25 years, he's still pretty much the justice he was in year one, and that's often not the case on the Supreme Court."

The 43-year-old rookie justice waited less than five months after his bruising Senate confirmation fight before casting his first solo dissenting vote. He argued that a prison escapee's membership in a white racist prison gang was relevant at his sentencing for murder, in part to help rebut testimony "that he was kind to others."

The lone dissent served as a marker that Thomas, whose elevation to the nation's highest court followed explosive allegations of sexual harassment, would not be cowed by criminals or colleagues. The defendant ultimately was executed. And Thomas has been dissenting ever since.

Now 68 and the court's second-longest-serving justice, the Georgia native remains known mostly for his contentious confirmation, his conservative record and his virtual silence during oral arguments, when his colleagues pepper lawyers at the lectern with interruptions. But he also is the court's strictest defender of the Constitution's original meaning, and it has led him to become a force on the far right flank.

Thomas has done little to counter his persona, declining most media interviews and speaking almost solely to friendly audiences. When he did speak to the National Bar Association, an African American group, in 1998, he decried the "bilious and venomous assaults" against him that implied "I have no right to think the way I do because I'm black."

But his defenders, including many of his former law clerks, are mounting a public relations campaign to tout his unique brand of jurisprudence. They've launched a website, JusticeThomas.com, in an effort to recast his legacy.

"Thomas has had this bull's-eye on his back his entire career," says Mark Paoletta, a former assistant White House counsel who helped President George H.W. Bush's nominee navigate past Anita Hill's nearly fatal harassment charges in 1991. "I don't think he's gotten enough credit. ... So many of the stories about him are negative."

Thomas' deep conservatism has made him a target of the civil rights community, embodied by the justice he replaced, Thurgood Marshall, who founded the NAACP Legal Defense Fund in 1940. He opposes racial preferences in college admissions and hiring, as well as drawing election districts to boost minority candidates. The new National Museum of African American History and Culture highlights Hill's allegations but ignores Thomas' 25 years on the bench.

That quarter-century is noteworthy for its focus on an arcane area of law — Thomas' opposition to what he sees as the illegitimate power of unelected bureaucrats. He rejects a string of Supreme Court rulings that granted federal agencies deference to interpret laws and regulations.

Randy Barnett, a constitutional law professor at Georgetown University Law Center, calls Thomas "a fearless originalist."

"He elevates the original meaning of the text above precedent," Barnett says. “In other words, he puts the founders above dead justices.”

'Exceeded expectations'

Bush's nomination of Thomas, a little-known federal judge and former Reagan administration official, reached pay dirt after a near-record 107 days and a historically narrow 52-48 Senate vote. Today the former president, now 92, remains proud of his pick.

"While Justice Thomas is known both for his consistently sober demeanor on the bench and his thoughtful and respected jurisprudence, he is also widely admired for his warmth among his colleagues, law clerks and the court staff," Bush said in a statement. "He is a very good man."

Thomas was raised by grandparents in the Jim Crow South of the 1950s, and at times he has revealed the same anger at racism and segregation felt by civil rights advocates. He dissented from the court's 2003 ruling that struck down Virginia's ban on cross-burning, calling the practice part of a "reign of terror ... intended to cause fear and terrorize a population."

But unlike the great majority of African-American lawyers, judges and public officials, he rejects the need for favored treatment of minorities. "Any effort, policy or program that has as a prerequisite the acceptance of the notion that blacks are inferior is a non-starter with me," he said in that 1998 speech.

Civil rights leaders "had him pegged, knew who he was, and that's exactly what he's been," says University of North Carolina School of Law professor Theodore Shaw, a former president of the NAACP Legal Defense and Educational Fund. While Thomas doesn't see eye to eye with the civil rights community on much, Shaw says, "his opinions are often forceful. Even if I disagree with them, I can't tell you that they don't have their own logic."

On issues from affirmative action and abortion to same-sex marriage and voting rights, Thomas has emerged as a solid conservative vote. His supporters insist those verdicts are based on originalism and textualism — following the words of the Constitution and federal statutes — rather than ideology. They note the same rigor led Thomas to defend state laws legalizing marijuana for medical use, despite his personal objections.

"He has exceeded all of our expectations," says C. Boyden Gray, who as White House counsel in 1991 played a major role in Thomas' nomination and confirmation. “His opinions are as lucid and as erudite as anyone's I can think about in recent years.”

Frequently, those opinions come in the form of dissents or concurrences, which lay out different reasons for reaching the court majority's verdict. In many cases, he wanted to reconsider the court's own precedents — something even Scalia was loath to do. "I'm an originalist, but I'm not a nut," Scalia often quipped.

“I do think in some ways Justice Thomas is a more thoroughgoing originalist than Justice Scalia was," says Neomi Rao, a former Thomas law clerk who directs the Center for the Study of the Administrative State at George Mason University's Antonin Scalia Law School. "Justice Thomas is more willing to go back and overturn precedents, to go back and find the original meaning of the Constitution.”

Thomas took Scalia's death in February hard, recalling at a memorial service the many "buck-each-other-up visits, too many to count" with "Brother Nino" when the two were on the losing side. It appeared he might emerge from a 10-year silence on the bench when he asked several questions in a gun rights case soon after Scalia's death, but he has not spoken up since.

Justice Thomas breaks 10-year silence in court

His opinions on sensitive race and gender issues have disappointed — but not surprised — civil rights and women's rights groups. When the court ruled 5-4 in 2013 that Southern states no longer can be singled out for federal oversight under Section 5 of the Voting Rights Act, Thomas said the entire provision was unconstitutional. This year, he dissented from the court's 4-3 decision upholding the University of Texas' use of racial preferences in admissions, arguing that all such policies violate the Equal Protection Clause.

Guy-Uriel Charles, founding director of the Duke Law Center on Law, Race and Politics, says for civil rights groups Thomas "fit into their greatest fears and deflated their greatest hopes in almost every single area ... If there is a justice from whom we’ve seen little evolution, it’s Justice Thomas."

“He is more of a private figure on the bench, but he certainly has not been retiring in the opinions that he’s written over time,” says Marcia Greenberger, co-president of the National Women's Law Center. She calls his views on equal protection and the right to privacy "very extreme.”

Workhorse, not show horse

Thomas has not authored the sort of landmark Supreme Court decisions that require delicate compromises to garner slim majorities. His role in writing more technical, often unanimous decisions is that of "a workhorse, not a show horse," says Harvard Law School Professor Mark Tushnet.

That's fine by Thomas, who has warmed to the task gradually over time. “I never thought that I would treasure doing my job, and I’ve reached that point,” he told a conservative Federalist Society dinner in 2013. "Even the most boring cases to others are fascinating to me.”

Those comments signified for many a change in attitude from the man who famously decorated his Yale Law School degree with a 15-cent sticker from a cigar package. The perception of racial preferences, he felt, had stolen its value.

"He really is enjoying himself," says Carrie Severino, a former Thomas clerk who is chief counsel at the conservative Judicial Crisis Network. Much like Mother Teresa, who put faith above success, Severino says Thomas relishes "fighting the good fight" even when he loses.

That was true the past two terms, when Thomas wrote 37 dissents and 25 concurrences, nearly twice as many as any other justice. On divided cases, he was on the losing side 58% of the time. If the court tilts to the left in the future, that percentage could rise.

“He’d rather be the Oliver Wendell Holmes of his time, the great dissenter,” says former law clerk John Yoo, a professor at the University of California Berkeley School of Law. "The more he might lose some of these issues, the more determined it’s going to make him to stay on the court.

"I think we're only halfway through the justice's career."