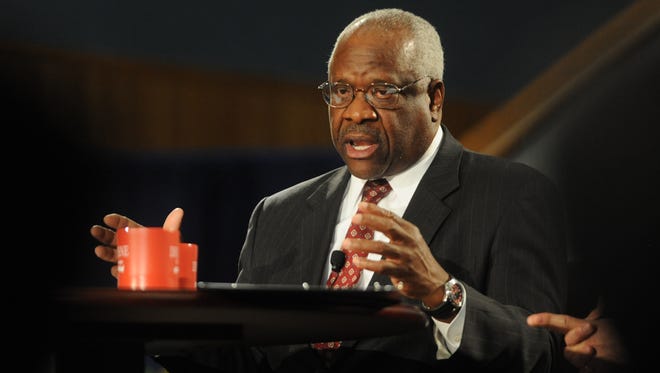

Court's lone black justice rails against 'racial quotas'

WASHINGTON — Supreme Court Justice Clarence Thomas has railed for decades against federal laws and court rulings requiring the creation and preservation of election districts dominated by minority voters.

Wednesday, the court's lone black justice blasted his colleagues' latest decision on racial gerrymandering — one that faults Alabama, in essence, for overdoing it.

By Thomas' reasoning, the state's Republican-run Legislature was following federal rules and high court precedents when it refused to dilute black voting strength in any of the 35 state House and Senate districts designed to elect black legislators. Those rules and rulings were misguided, he said — but the fault belongs to Congress, the Justice Department and the Supreme Court.

"The practice of creating highly packed — "safe" — majority-minority districts is the product of our erroneous jurisprudence, which created a system that forces states to segregate voters into districts based on the color of their skin," Thomas wrote in a lone dissent. (He also joined three colleagues in dissenting largely on procedural grounds.)

Thomas' position on racial gerrymandering, like his opposition to affirmative action, is long-standing. The court's 5-4 ruling against Alabama's maps — because they may have packed too many blacks into some black districts — gave him a new reason to denounce an old policy.

The original purpose of the 1965 Voting Rights Act, he said, was to prohibit practices that denied minority citizens' access to the ballot, such as literacy tests. So far, so good.

In recent decades, however, the Justice Department and the courts used the law to police how state and local governments draw political districts, ensuring minority voters can elect minority candidates. As Thomas sees it, that's when the law and its legal interpretations went off the track.

The ironic twist in the challenge brought by black and Democratic lawmakers — that the 2012 state redistricting plan was illegal because it put more blacks than necessary into some districts, thereby diluting the impact elsewhere — rendered Thomas apoplectic.

"We have somehow arrived at a place where the parties agree that Alabama's legislative districts should be fine-tuned to achieve some 'optimal' result with respect to black voting power," he wrote. "The only disagreement is about what percentage of blacks should be placed in those optimized districts. This is nothing more than a fight over the 'best' racial quota."

States such as Alabama, Thomas concluded, have been "whipsawed" — first forced to create majority-black districts, then told not to diminish black voting strength, and finally told they've been too rigid in that task.

"I do not pretend that Alabama is blameless when it comes to its sordid history of racial politics," he said Wednesday on the 50th anniversary of the Selma-to-Montgomery voting rights march. "But today, the state is not the one that is culpable."