New breed of VR pushes for social change

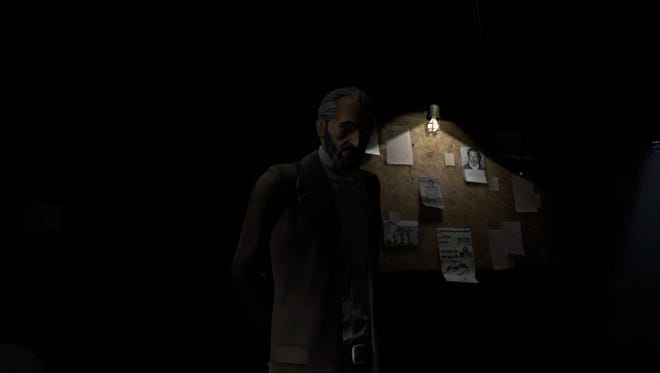

As you play the new virtual reality video game Blindfold, a grim prison interrogation room wraps around you in full-scale, 360-degree dread. Somewhere off in the distance, a prisoner screams.

It’s the early 1980s, and you’re a captured photojournalist in Iran’s notorious Evin Prison, being interrogated for providing pictures to Western news outlets.

Confess and you may be spared. Antagonize your tormentor, modeled after one of Evin’s actual interrogators, and he may turn to the battered companion who gave you up and execute him on the spot.

Stop this game, I want to get off!

Debuting Wednesday in the U.S., the brief, 12-minute Blindfold is one of a new breed of immersive, sometimes terrifying experiences that bend the rules of virtual reality (VR) and augmented reality (AR) to tell serious stories. In much the same way that game designers for years have used flat-screen media to teach about history, science, politics, culture and current events, VR storytellers are now finding ways to use the power of immersion for nothing less than understanding, empathy and social change.

“We were very invested in this idea of journalism and journalists and the price that they pay, particularly in hostile governments who are not supportive of free press,” said Vassiliki Khonsari, a Greek-American filmmaker and one of Blindfold’s developers.

Ink Stories, the New York media startup that she runs with her husband, the Iranian-Canadian game designer Navid Khonsari, also created the critically acclaimed video game 1979 Revolution, about the Iranian Revolution. She calls Blindfold a “sister piece” to 1979.

After Blindfold’s U.S. debut, Ink Stories will give it away to anyone with an Oculus Rift or similar VR gaming rig. “It’s something we want audiences to experience and we believe in the value of it,” Khonsari said. “We want to reach as many audiences as we can.”

Blindfold, along with nine other experiences — including a short VR film exploring a Syrian 12-year-old’s life in the Za’atari Camp in Jordan — will be on display in New York on Wednesday for the first-ever VR for Change Summit, a one-day event that is part of the larger Games for Change (G4C) Festival, which began Monday. The festival turns 14 this year.

That G4C is embracing VR was perhaps inevitable — for years it has hosted VR experiments, said Susanna Pollack, the festival’s president. “For me it felt like a natural extension of what we’ve been doing.”

But just as significantly, she said, over the past few years many VR developers have been “going beyond games,” experimenting with the best uses for VR. Game designers, filmmakers, journalists, artists and researchers have all pushed the field forward in unexpected ways, she and others said.

“A lot of the really exciting stuff is when parts of those communities come together,” said Erik Martin, who is curating Wednesday’s summit.

The event actually grew out of work the White House did last summer while Barack Obama was still president and Martin was a policy adviser in the Office of Science and Technology.

Obama had appeared in a well-received National Geographic VR film and got interested in using the technology for social impact. That led Martin to work with the U.S. Department of Education and Luminary Labs, a consulting firm, to create an “EdSim Challenge” that encouraged developers to create VR and AR tools for career and technical education.

Now a senior education program manager at Unity, the gaming platform, Martin said the power of VR is that it “forces you to pay attention to the thing in front of you, or that you are literally inside of.”

He noted another piece on display Wednesday, Across the Line, by “immersive journalism” pioneer Nonny de la Peña. Commissioned by the Planned Parenthood Foundation of America, it puts viewers in the role of a woman facing down protesters at an abortion clinic.

Though it’s not on display this week, Out of Exile: Daniel’s Story, uses real audio of a gay teen coming out to his family, who verbally and physically attack him. De la Peña’s Emblematic Group worked with Daniel Ashley Pierce, who'd captured the audio on his phone, to create a virtual version of the confrontation.

Martin, 23, who came out to his family at 18, said Out of Exile was powerful. Coming out, he said, “really is a thing that feels like jumping off the edge of a cliff — that’s very hard to convey to other people unless they experience that cliff-drop feeling, even a little bit.”

In many ways, VR is the perfect medium to help people understand another’s experience, said Stanford University researcher Jeremy Bailenson, founding director of Stanford’s Virtual Human Interaction Lab.

Much of what gives VR its power is its ability to create "presence," the feeling that you’re in a scene and that it’s reacting to you in real time. If a scene moves naturally, smoothly and seamlessly as your head and body move, the simulation essentially fools your brain into believing that you’re in a real experience, not a simulated one.

The effect can be unexpectedly powerful. In Clouds Over Sidra, the VR film about a Syrian 12-year-old’s life in the Jordanian refugee camp, the act of sitting in on a simple family meal, in a spare temporary shelter, is almost unbearably moving.

Years before consumers could buy an Oculus Rift on Amazon for $399, Bailenson was at work creating powerful, if expensive, simulations in his lab with elaborate VR rigs. In one of his most well-known experiments, Bailenson put users through the paces of virtually cutting down a mighty sequoia and watching it crash in front of them — the tree cracked audibly and the lab floor shook on impact. Later, those who did the cutting used less paper in the real world than those who had only imagined what it would be like to cut down such a tree.

In another experiment, Bailenson, along with researchers from UCLA and Microsoft Research, showed college students photos of themselves, but digitally altered half of them with gray hair and a 65-year-old’s facial features. Asked how they’d spend a $1,000 gift, those who saw their aged selves said they’d put more than twice as much money toward retirement as the control group.

In his spare time, Bailenson also runs a startup that uses VR to train athletes, retail workers and others. Among its recent clients: Walmart, which now trains floor employees on how to respond to the annual "Black Friday" rush with a VR simulation.

But that power to change minds can sometimes be too powerful, Bailenson said. “In VR you should do things that you couldn’t do otherwise, but I don’t believe in VR that you should do things you wouldn’t do otherwise.”

As an example, he strongly cautions film directors against putting viscerally powerful scenes of carnage into VR experiences, especially those with “haptic” feedback that simulates touch or vibration, as in his lumberjack simulation. Jaws is a great film, he said, but if we’d all seen it in VR, none of us would ever dip our toes into the ocean again.

“Sharks on the screen are fine,” Bailenson said. “Sharks biting your leg and you feeling your leg go off is probably not something you want to do.”

So what about torture in an Iranian prison?

Khonsari said she and her colleagues trod lightly. The scene is animated, not live-action, and the game gives players just enough agency to keep from feeling helpless — they interact with the interrogator by looking at him or elsewhere, and by nodding or shaking the head to indicate “Yes” or “No.” But if players nod their heads too quickly or hesitate too long, the game responds differently.

“If it’s done in a thoughtful way, the rewards can be impactful and great and spark a shift in thought,” Khonsari said. As with de la Peña’s coming-out piece, VR “can communicate an experience like nothing else” — in this case the plight of imprisoned journalists.

For the game, Ink Stories partnered with the Committee to Protect Journalists and the Center for Human Rights in Iran. At the end of Blindfold, the lights go down, then come back up for a sort of grim curtain call: The entire 360-degree field of view is filled with the faces and names of real journalists who have been imprisoned and sometimes killed, from Iran to Egypt to Mexico, China, Colombia, Turkey, Saudia Arabia and beyond.“Some who have survived and some who haven’t,” Khonsari said.

“If you haven’t found the value up until that point," she said, "then it really rings as important.”

Follow Greg Toppo on Twitter: @gtoppo